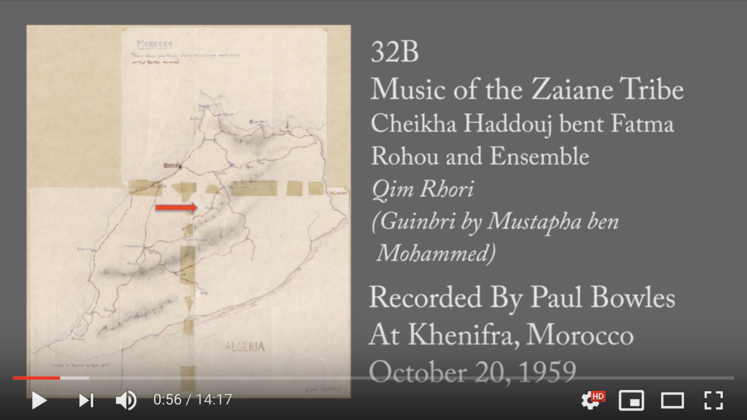

In making available on Archnet the complete recordings of Moroccan music made by Paul Bowles between 1959-1962, we decided not to do any significant editing of the recordings, aside from deleting completely quiet space at the beginning or end of each digitized file. The collection is meant to represent the archive, held by the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, as it is. As a result, you can sometimes hear sounds such as the banter among the artists that you occurs at the beginning of this recording made in Khenifra in October 1959.

We’ve been working on bringing these recordings to Archnet for nearly 5 years. Videos had to be created for each track, and each video had to be linked to the corresponding notes, locations, authorities, and related recordings. To make things even more challenging, the digitized files were out of sequence and incorrectly named. Now, at last, you can hear all the recordings without getting your hands on the original tapes or the digitized files. It is worth noting that the digitized files were created and brought to my attention after several years of efforts by Gerald Loftus, then director of the Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies to bring the recordings to the attention of the public. Read more about that on the TALIM website.

Personally, I find fascinating the unintentionally captured bits of sound you can hear on these recordings. Whether it is dogs barking, engines starting, chairs moving, people talking, or the sounds of the musicians tuning, each sound is evocative, and tells its own story. Many of those stories are illuminated in the notes that Bowles typed up on onion skin paper. His comments are apologetic in tone, as his goal was to capture the music and these sounds interfere with that, but I am intrigued by the slices of life that he inadvertently recorded. The recordings made at festivals or in the midst of the city during a call to prayer are highly evocative of the time and place in which they were recorded, and often as interesting as those recorded under more ideal circumstances.

In total the are about 70 hours of music constituting an amazingly rich and varied collection of music: religious and secular; “art” and popular music; Jewish and Islamic; and Amazigh, Arabic (both Moroccan and Classical), and Hebrew. This eclecticism stems from a variety of influences, too. For example, the gnaoua music is closely tied to Sub-Saharan Africa, whereas the Andalusian music is connected to Islamic Spain.

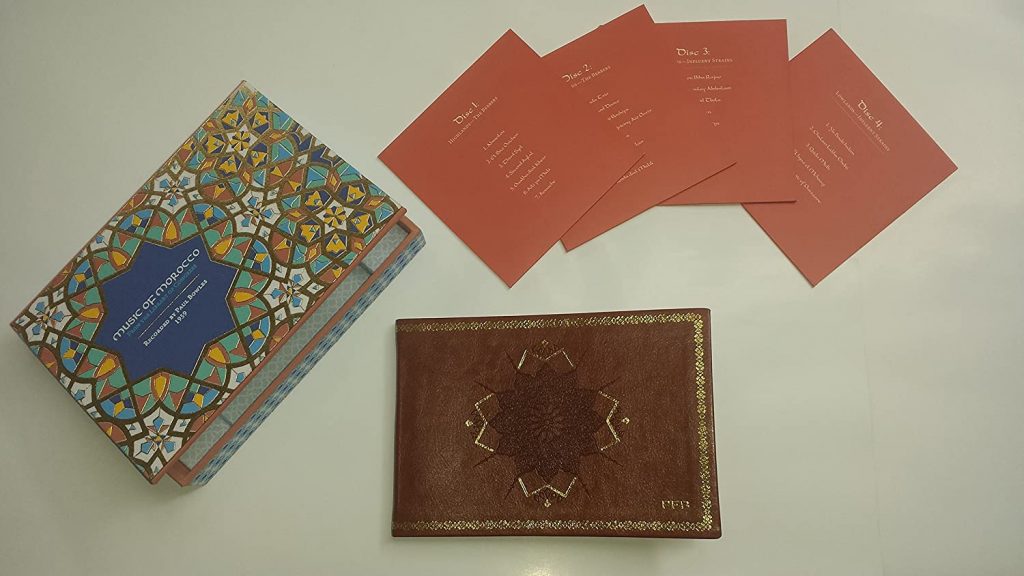

That said, because we didn’t clean them up, one has to listen very carefully to hear the musicality of these tracks. A contemporary sound engineer could bring out the sounds that Bowles was actually trying to capture, separating them from the rest. That is very well done on the 2016 Dust-to-Digital box set of CDs “Music of Morocco from the Library of Congress” (also available digitally) containing a representative sample of the recordings. Produced by ethnomusicologist Philip D. Schuyler, the collection contains remastered recordings of the tracks included on a 1972 vinyl release, plus a carefully chosen selection of additional recordings chosen from the tapes.

The remastered tracks highlight the music itself, removing all the superfluous noise and adjusting sound levels to compensate for the less than ideal conditions in which the original tapes were recorded. The music itself emerges with remarkable clarity, making this collection a much more pleasurable listening experience that the tracks in the Archnet collection.

The 120-page booklet that comes in the boxed set is handsomely bound in leather, but it is also available as a PDF with the digital download of the music. It contains an extended, insightful essay by Philip D. Schuyler, and supplements the notes made by Bowles with additional commentary. In the interests of accurately representing the collection and due to time constraints, the cataloging of the Archnet collection sticks very closely to the notes made by Bowles himself, reflecting the spelling and naming conventions, as well as the biases and misconceptions, of the time. In the booklet Schuyler also presents these notes as written by Bowles, but he adds additional information and commentary that is informative and insightful.

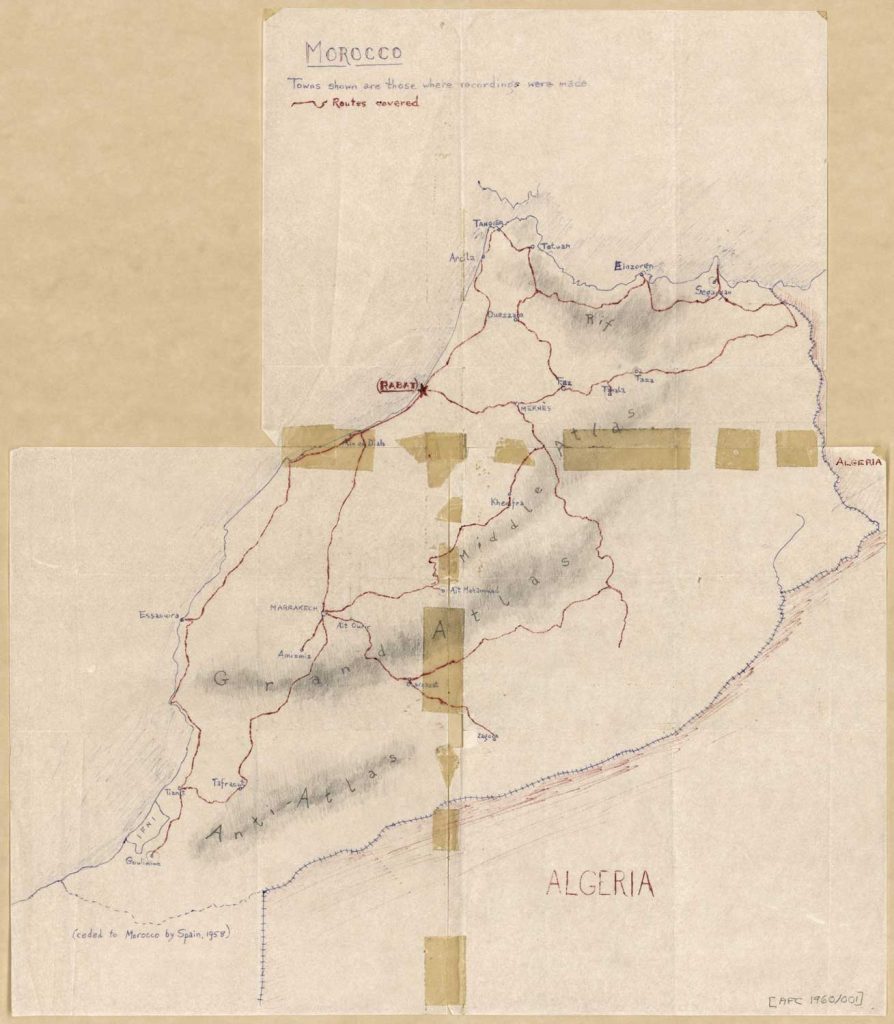

In 1959, just 3 years after Morocco gained its independence, Paul Bowles, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Library of Congress, performed a tremendous service, traveling as much of the length and breadth of Morocco as was possible at the time to record a representative sampling of the nation’s music. Philip Schuyler has done an outstanding job selecting and re-presenting the best of those recordings for the Dust to Digital collection. Now the Aga Khan Documentation Center, MIT Libraries, is thrilled to have brought the entire collection, originally digitized under the auspices of the Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies, to the world on Archnet.org. Happy listening!